Lessons from Abraham Lincoln on turning depression into a superpower on the eve of a stressful hour in our Republic

At Ford’s Theatre Center for Education and Leadership in Washington, D.C., visitors encounter a overwhelming visual — a 34-foot tower of books written about Abraham Lincoln, 6,800 titles representing well under just half of the 15,000 volumes published on the Great Emancipator.

So it seems something of a fool’s errand to pluck just one of these books — as if in a game of Jenga.

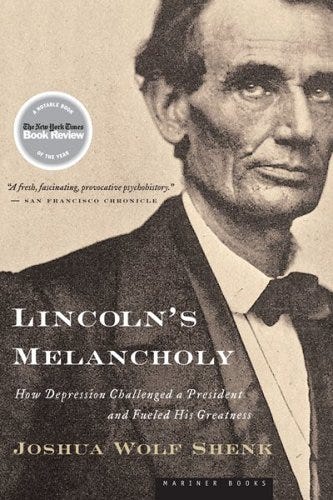

But a book (among many) that stands out is Joshua Wolf Shenk’s 2005 “Lincoln’s Melancholy: How Depression Challenged a President and Fueled His Greatness.”

“Lincoln didn’t do great work because he solved the problem of his melancholy,” Shenk writes. “The problem of his melancholy was all the more fuel for his great work.”

In reading Shenk’s book — and knowing the popular culture’s treatment of mental illness — it is hard to imagine one of our greatest presidents getting elected as a state legislator — much less ascending to the lead the nation. Pop culture, it’s sad to say, drum-majors the modern American parade.

Imagine a presidential candidate dealing with the unspooling of stories of suicidal thoughts, of retreat into gloom?

In 1835, Anna Mayes Rutledge, a young woman for whom Lincoln held affection died (probably from typhoid).

Lincoln’s friends were concerned he may commit suicide because of the anxiety and depression associated with the loss. They reportedly even locked him up to prevent suicide or “derangement,” Shenk writes.

Lincoln “told me that he felt like committing suicide often,” recalled Mentor Graham, according to the book.

Robert L. Wilson, who ran for the Illinois Legislature with Lincoln in 1836, made this observation: “He sought company, and indulged in fun and hilarity without restraint or stint as to time. Still, when by himself, he told me that he was so overcome with mental depression that he didn’t dare carry a knife in his pocket.”

But the depression served as what Byron described as a “fearful gift.” It was awful burden for Lincoln, but the gift element was a capacity for depth and even genius.

In many instances, Shenk notes, depressive may actually be taking a more accurate accounting of the world and their places in it. They don’t drink the Kool-Aid, either of their own making, or their image machines.

Lincoln told one of his closest friends, Joshua Speed, that he could kill himself, but wanted to “link his name with something that would redound to the interest of his fellow man.” Shenk writes that the psychologist Hagop S. Akiskal takes the position that depressives “seem to derive personal gratification from over-dedication to professions that require greater service and suffering on behalf of other people.”

Bill Clinton was famous for “feeling your pain” as a political strategy, a marketing approach. Surely there is some substance with the style. But with Lincoln, it was there, etched on the iconic pained face.

Today, Lincoln would be dismissed, with barbed jokes from the left and righteousness from the right, as a candidate seeking to run for the presidency of Prozac Nation. But Shenk believes it assisted Lincoln in the 19th century.

“While many found his moods odd and curious, the most common reaction was positive interest,” Shenk observes.

And, of course, a great question rages: Had Lincoln been able to avail himself of modern management for depression, would we have had Lincoln?

He embraced the depression, owned it — and in the fight, saved the Union. His own survival, according to Shenk, depended on an obsessive commitment to a cause outside of himself, for living an inwardly directed life (the stuff of modern suburban consumptive isolation) would have been his ruin.

NOTE: The Iowa Mercury is on the verge of hitting 100 paid subscribers and closing in on 1,500 total subscribers. Please consider helping us expand the reach of the work in the state by becoming a paid subscriber. There could be dinner in it for you.

(Douglas Burns, founder of The Iowa Mercury and a fourth-generation Iowa journalist from Carroll, is a member of the Iowa Writers’ Collaborative. Read dozens of the most talented writers in Iowa in just one place. The Iowa Writers' Collaborative spans the full state. It’s one of the biggest things going in Iowa journalism and writing now — and you don’t want to miss. This collaborative is — as the outstanding Quad Cities journalist Ed Tibbetts says — YOUR SUNDAY IOWA newspaper. )

Save the Date for a Holiday Party! Friday, December 13, 2024, 5-8 p.m.

The Iowa Writers Collaborative will host a party at the Harkin Institute on the Drake University campus in Des Moines, Iowa. The event will include appetizers and a short program. It’s a great opportunity to meet some of your favorite writers and visit the state-of-the-art home of the Harkin Institute for Public Policy & Citizen Engagement.

Please become a paid subscriber to any of our columns, including this one, and RSVP here. A donation will be accepted at the door for spouses or guests. If you’re traveling, see hotel information on the RSVP form.

Details:

When: 5-8 p.m. Dec. 13, 2024.

Where: Harkin Institute, 2800 University Ave., Des Moines.

What: Appetizers, a short program, and great conversation.

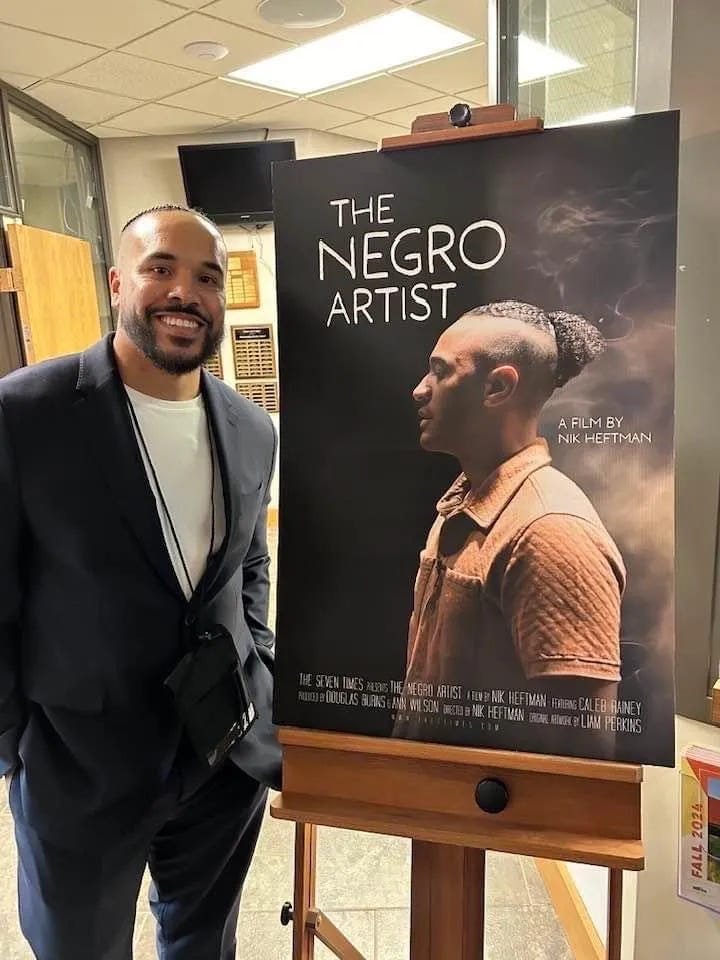

Go see Iowa filmmaker Nik Heftman’s documentary “The Negro Artist” in Iowa City (other locations announcing soon)

In another Iowa Mercury piece Douglas Burns writes about fellow Iowa Writers' Collaborative member Nik Heftman's documentary. "The Negro Artist" will be shown at numerous theaters and locations around the Des Moines metro area in coming months. It's also showing at 7 p.m., Dec. 11 at Film Scene in Iowa City. For showtimes in Iowa and across the nation please visit The Seven Times website. — Or click below.

Walls in the Springfield, IL Lincoln Museum have copies of political cartoons lampooning Lincoln. He faced national and personal challenges and public vitriol. A lesson from Lincoln and the reported book is how personal inner strength and resilience manifest. Illness does not equal weakness. Thanks Doug, a good reflection as we face election chaos.

I've known plenty of great, pro social people, who struggle with depression. I wish there wasn't still so much stigma about that with people running for office. I still remember all the uproar over Tom Eagleton as McGovern's VP pick, and how much that was used against McGovern, helping us end up with Nixon and our first criminal president who had to resign in disgrace. Set the stage and bar low for Trump later on..